Ideally, when I am portraying a patient in pain, my portrayal will give student doctors a clue as to how much pain I am in. But students are also trained to ask the classic question: "Can you rate your pain for me?"

|

Classic universal pain scale via nshealth.ca.

[click to embiggen] |

Above is the classic pain scale. However, instead of saying "zero being no pain and 10 being the worst pain possible" students often say, "where 0 is no pain at all and 10 is the worst pain you've ever felt." I always think this is a little limiting, because the scale could change for each patient depending on how much pain a patient has experienced in a lifetime. For instance, a patient who has given birth may rate an ankle sprain at a 6, whereas someone who has sprained an ankle may rate it a 10 if nothing else worse has happened to them. Cases are written so that all patients give the same rating, but when the question is asked this way, as an SP I always have to think about it: what

is the worst pain I've ever felt? (

Pulmonary embolism, in case you're wondering.)

Sometimes, student doctors will simply ask "Can you rate your pain on a scale of 1-10" and I have learned to ask "Is 10 bad or is 10 good?" to remind them they haven't given the patient a complete scale. Because outside of the simulation, if a doctor doesn't clarify, the patient may give what s/he considered to be a reasonable guess, and the doctor may get incorrect information.

Badly written cases will often only have one pain rating attached even though the pain has changed over time. So if student doctors ask questions like "What did the pain start at?" or "How long has it been at a 4?" as an SP I always wince and guess. The rule of responding to cases that don't have a definitive answer to a student question is that the answer is either "no," "I don't know," or that the answer won't affect the case. But I certainly feel like a better SP and more standardized when I know the answers to good questions.

I say our affect should be an indicator to the patient's pain level, but only one school I work with attempts to standardize SPs to portray pain based on the case rating -- and then usually only for the really important cases that could affect a student continuing with the program. This can make it more difficult for student doctors to interpret my pain, because other SPs may portray a 6 less seriously than I do. Some students may feel I am "overacting" if I portray a 6 with a "wrinkled nose, raised upper lip, rapid breathing," even though that's the official pain scale.

However, my favorite pain scale is from

Hyperbole and a Half:

|

0: Hi. I am not experiencing any pain at all. I don't know why I'm even here.

1: I am completely unsure whether I am experiencing pain or itching or maybe I just have a bad taste in my mouth.

2: I probably just need a Band Aid.

3: This is distressing. I don't want this to be happening to me at all.

4: My pain is not fucking around.

5: Why is this happening to me??

6: Ow. Okay, my pain is super legit now. |

|

7: I see Jesus coming for me and I'm scared.

8: I am experiencing a disturbing amount of pain. I might actually be dying. Please help.

9: I am almost definitely dying.

10: I am actively being mauled by a bear.

11: Blood is going to explode out of my face at any moment.

Too Serious For Numbers: You probably have ebola. It appears that you may also be suffering from Stigmata and/or pinkeye. |

This scale is the one that most closely matches how I actually feel about pain in my own life. Honestly, if I rate something as a 9, I want the doctor to know I feel I am almost definitely dying. Few people go to the doctor unless the pain is at least a 3 or more. So even though a 3 is considered "mild" pain in the classic scale, it's significant enough to drive the patient to see a doctor. In other words, the pain is bad enough for someone to miss work and/or pay a lot of money to address it. At that point, no pain is "mild" pain, in my opinion. As a patient, one of my biggest fears is that the doctor won't take my pain seriously. I worry they may think a 6 is mild, even though, as the Better Pain Chart shows, I feel like "my pain is super legit now."

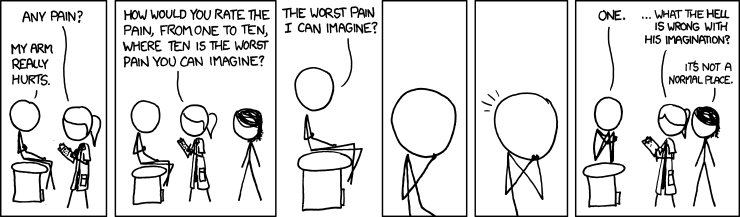

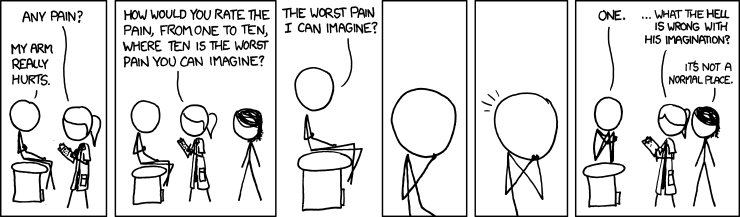

Sometimes, students describe the pain scale "where 0 is no pain at all and 10 is the worst pain imaginable." When they do, I smile to myself and think of

this xkcd comic:

|

| [click to embiggen] |

I can imagine a LOT of pain. Cases always have pain ratings attached to them that won't fluctuate based on how students ask this question, but when the scale is described to me this way I think, if I were a real patient, I would drastically revise my estimate downward.

Extra credit!

If students ask about the

ADL scale right after the pain scale, it can be very confusing for patients because the scale is reversed. When that happens, I think it's better to ask about it as a percentage than a single number.

Postscript (Jun01.2020):

When the coronavirus devastated the profession, this pain scale felt especially appropriate: