|

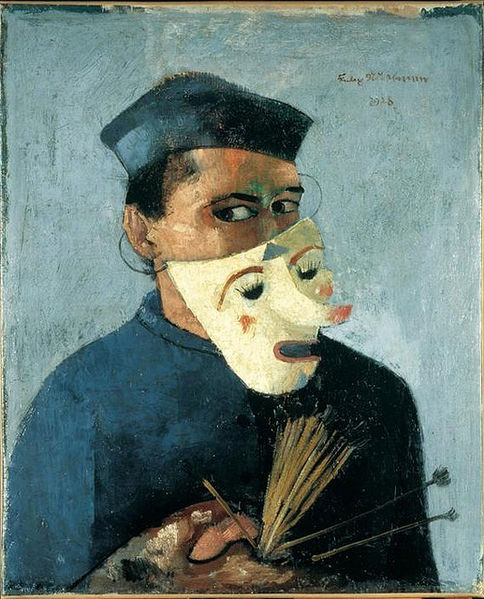

| An elderly patient patiently waits for her appointment. [Portrait of an Old Woman via wikimedia] |

Some people still say you can't practice empathy, that people either have this as a skill or they don't. I disagree, which is why I like these elderly simulations in Poland:

Medical student Ludwika Wodyk fumbles her way slowly down the stairs, her movements encumbered by heavy strapping around her limbs and body, her vision distorted by special goggles. She is one of a group of medical students in Poland being given the chance to experience first-hand how it can feel to be an aging patient.Empathy is something that can be taught, or at the very least, experienced. For many people, empathy is highly contextual, so direct experience with a problem can often give them insight into the barriers or complications of a particular population. This brings benefits like understanding, tolerance, and more creative problem-solving when the same circumstances arise again.

Elderly simulations can also be found in Britain and at MIT.

Extra credit:

When I roleplay older patients, I usually focus on the visual aspects. In future scenarios I want to pay more attention to the physical aspects and give feedback from the perspective of a person who might also have mobility, sight and hearing challenges as well.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/1599px-Carl_Larsson_-_Self-Portrait_(In_the_new_studio)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg/800px-Zampieri_-_Adam_et_%C3%88ve_(d%C3%A9tail).jpg)

%2C_Artemisia_Gentileschi.jpg/425px-Susanna_and_the_Elders_(1610)%2C_Artemisia_Gentileschi.jpg)