|

Looks pretty simple, doesn't it?

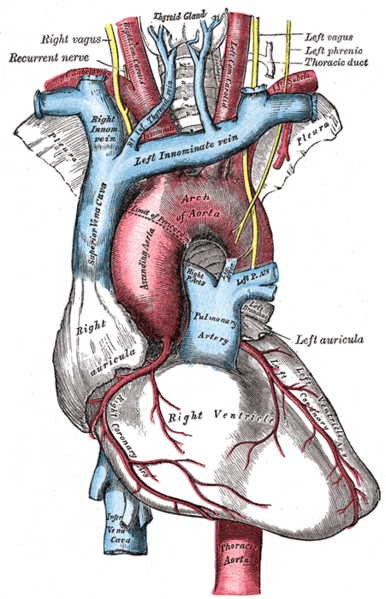

[from Bell's Explaining the Course of the Nerves via wikimedia] |

In the "classic" SP encounter, I am tasked to memorize a case, act it with the students, keep track of what the student is or isn't doing while in the encounter, complete a checklist after the student leaves, and then give feedback to the student after the checklist is complete. Wash, rinse, repeat up to 20 times a day.

Of those types of cases, the hardest one is the neuro case, because the neuro exam has

so many things to remember. Most physical exams have a limited number of discrete actions on a small segment of the body. The neuro exam, however, is literally head to toe. A complete neuro exam can include as many as 40 items -- on top of memorizing the history and communication checklists!

And for patients, the neuro exam is often the most obtuse exam. The other exams are generally pretty obvious: if I come with stomach pain, I expect the student to do an abdominal exam. But neuro exams can be used for several cases, including headaches, seizures, palsy, strokes, hypertentions, stress, cardio, confusion, etc.

So when students don't explain what they are looking for, parts of the neuro exam can feel like complete nonsense. My doctor wants me to do what? And what does it have to do with the problem I came in for? Without appropriate expectations management, this can erode my trust and confidence in the student doctor. Plus, since students primarily practice on each other, they anticipate the next step in the process and forget the patient doesn't know it. So when I give feedback after neuro exams, it's primarily focused on expectations management,

autonomy and

consent.

Here are some of the things I am looking for during a neuro encounter:

This is a living list. Last updated Apr09, 2014.

- Associated symptoms: When students ask only about associated symptoms, I have learned to say "Like what?" so that I don't inadvertently give something away. When students ask about "auras" without explanation, as a patient I find that really confusing, and I may suddenly wonder if I am visiting a New Age doctor instead of an MD. When students ask about "visual changes" I don't know how to answer unless they give examples.

- Eye movement: students almost always forget to tell me to follow the movement of the pen with my eyes only. If they tell me to follow the pen, I move my whole head and wait to see if they notice. Some don't -- which means I can't give them credit for doing an H exam. Most do, and when they stop to give me clearer instructions without apologizing, as a patient I often feel both embarrassed and annoyed.

- Checking visual fields: If a student asks "Do you see my fingers?" I turn my head to look at them. Yep, I see them. Tell me where to look if it matters!

- Shining a light in my eyes: tell me where to look. If you don't have to use the very brightest setting, please don't.

- Examining eyes with ophthalmoscope: tell me where to look. Also, tell me you're going to get so close to me before you do, or I might start backing away. Never touch my lips with your finger to brace yourself. If you're going to use my forehead to brace yourself, warn or ask me before you do it. If you're going to lift my eyelid up, definitely warn me -- but I recommend checking without lifting first to see if you can get what you need in the most minimally invasive way.

- Using a Snellen chart: if a student asks me to "read the smallest line" I read the text on the bottom of the card. Be specific if it matters!

- Checking hearing: I feel more comfortable if I am able to cover my ear rather than the student doctor doing it. If I can see the student doctor's hands while they rub their fingers together, that can affect the outcome of the exam. If a student doctor rubs their fingers together but doesn't ask me if I hear it, I do not respond. I really appreciate when students use words like "taco" or "raspberry" during the whisper tests rather than "ABC" or "123." I feel more comfortable during the Weber or Rinne tests when the student doctor clearly explains why and how they are using the tuning fork.

- Facial expressions: This is the part of the exam where I feel like I'm on Candid Camera. Tell me why you want me to make funny faces for you. Do not use the words "innervate" when you do. Some variation of this is fine: "I'd like to test some nerves in your face, so I'm going to ask you to make a few funny expressions. Can you [smiles/frown/etc]?" If the student-doctor does it with me, I don't feel quite as ridiculous. If the student-doctor asks me to puff out my cheeks but does not tell me to keep them puffed as they push them, I will let them collapse -- which sometimes leads students to believe there is a finding when there isn't.

- Opening eyes against resistance: Quite often, students ask me to close my eyes and then try to open them without warning me. As a patient this Freaks. Me. Out. Feeling fingers against my closed eyes is very alarming because eyes are so vulnerable. But here's what's worse: opening my eyes as the student is reaching for them because as a patient I didn't know there was more to the test beyond closing my eyes. Either way, as a patient I WILL flinch. If done inadequately, this test can make me feel extremely vulnerable and unsafe with the student doctor. If it has been prefaced by other tests that have affected my trust, this one has an even bigger impact.

- Checking for sensation: "Can you feel this?" is not the same as "Does this feel the same on both sides?" And if you just ask "Does this feel the same?" I am likely to say, "The same as what?" unless you've specified comparison on both sides. When student doctors don't warn me before checking for sensation on my arms/legs, it can feel a little creepy, especially when the person is of the opposite gender. When checking for facial sensation, if a student reached towards my eyes before telling me about the facial sensation test, I will often move my head because as a patient I have no idea why they are reaching for a vulnerable area.

- Tongue deviation: "Stick your tongue out" can feel weird unless the student explains why (hopefully as part of the facial expressions). If you want me to open my mouth, tell me. Also, "Wiggle your tongue around" is not the same as "Move your tongue from side to side."

- Gag reflex: Schools have a lot of different policies on this. Some specifically ask student not to do it, some ask the SPs to fake a gag reflex as soon as it is clear that's what the student is testing for. And sadly, some actually want their students to actually test the gag reflex. I have a lot of tolerance for internal exams, but when that happens I fake the gag reflex immediately.

- Resistance tests: I feel very strongly that all resistance tests should be framed simply as "Push/pull against me" rather than "So I'm going to try to put your [body part] into [a position]. Don't let me." or "Resist me." The negative instruction makes me spend an extra second or two trying to figure out what the student doctor wants me to do. Additionally, it makes it much harder to when the actual test begins, because students are generally already holding my body in the position they want me to resist before they finish the instruction. It's as complicated to write as it is to work it all out on the table.

- Shoulder/neck resistance: With shoulder resistance, students often start by pushing down on my shoulders and when I don't automatically push up, they then have to explain the test. Sometimes they will tell me to lift my shoulders up and then push down on them -- without telling me to resist, so I let them push me down. Some students interpret this as a positive sign. The easiest way to perform this test is for the student to push down on my shoulder and say, "Please shrug your shoulders." Relatedly, if a student asks me to "Turn your head into my hand," as a patient I don't know whether they want me to rotate my head or tilt it towards my shoulder.

- Leg resistance: Don't ask me to push up both thighs against resistance at same time. Seriously, have you ever tried that? Do one at a time.

- Sharp/dull testing: For goodness sake, demonstrate sharp/dull testing once on my arm before going through the whole thing so I know what to expect. This is a million times more important if you're going to do it on my face. Also, do not be surprised when different parts of my body are more sensitive than others. That does not indicate a positive finding -- it just means jabbing me on the top of my foot with the same force as the outside of my thigh hurts more because the nerves are closer to the surface of the skin. If you are too tentative with your sharps, though, you may get false dull patches -- as an SP I am dying to tell you when that happens, but as a patient I just assume that's part of the test. If, as a patient, I have findings during a sharp/dull test, I often act surprised unless the patient has already observed it in the case history. That often prompts students to check again -- and if I give them an answer they expect, they cannot resist saying "yes, that's right." If the school has the student use a safety pin (?!!!) and the student has not shown it to me but I see it after the test, as a patient I will feel alarmed and betrayed. If my hand is not in the right position and a student moves it into position without asking while my eyes are closed, I will feel especially vulnerable.

- Reflexes: The thing I hate most about reflex testing is that almost every student grabs my arm without asking me or telling me why -- and I hate it even more so when they grab my hands (thumbs up). Moving a patient without their consent violates bodily autonomy, and as a patient it teaches me you do not value my consent. It is SO EASY and vastly more respectful to ask "Could you please place your arm here [indicating their own arm and waiting]? Okay, now relax your arm." Also, as an SP I have excellent reflexes (in both upper & lower extremities), so it is disheartening to discover lots of students are not able to elicit my reflexes correctly.

- Point-to-point and Rapid alternating movement: When students don't explain rapid alternating movement, I feel like I'm playing a child's game. This is especially true for the finger-to-nose test: as a patient, I wonder if the student doctor think I'm drunk.

- Orientation questions: When students ask me orientation questions without explanation, it seems unnecessarily ominous and obscure. Some are at least aware enough to say, "I'm going to ask you some silly questions." But rarely do they say why. Try "...to rule out anything serious." Afterwards, I would feel relieved if I was jokingly congratulated for passing this most obvious of exams.

- Gait and balance: "Hop off the table" seems a bit too informal for my tastes. Clear instructions about how to walk and how far to walk and why make me feel more comfortable.

Extra credit!

Because the neuro exam has so many items, students often feel rushed. That makes me feel anxious. As the exam progresses, the accumulation of abrupt and opaque exams can foster distrust -- which makes me feel even more anxious and cautious. And the more time student have to spend explaining or re-explaining the tests, the more rushed they feel. So the more students can pre-invest in finding simple ways to explain and manage the neuro exam for SPs, the faster and easier it will be for everyone, including the patients they see later in their careers.

.jpg)

.jpg)